Spain Is Doing Something Brave

Spain’s new amnesty law, on its way to the statute books after passing Congress in December, has ignited quite a ruckus. Tens of thousands of people have taken to the streets to protest the law — which provides a blanket pardon to hundreds of politicians, civil servants and ordinary citizens caught up in the illegal referendum on Catalan independence in October 2017 — and a majority of Spaniards oppose it. Many commentators and politicians, mainly on the right, have argued that the amnesty weakens the rule of law in Spain and even imperils the country’s democracy.

Much of the anger stems from how the amnesty deal came about. Socialist Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez promised during his electoral campaign last summer that there would be no blanket amnesty, even though he had pardoned nine Catalan separatists in 2021. But after an inconclusive election result left Mr. Sánchez needing the support of Catalonia’s separatist parties to secure a parliamentary majority, he changed tack and introduced the law. That it also applies to Spain’s Public Enemy No. 1 — Carles Puigdemont, the former Catalan leader who authorized the referendum and has been a fugitive from Spanish justice since 2017 — only intensified the bad feeling.

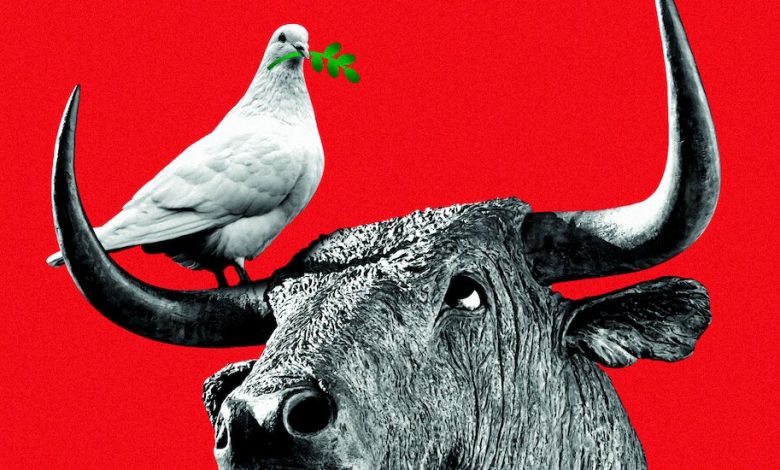

Yet despite the stench of political opportunism that hangs around Mr. Sánchez’s amnesty deal, this is a bold — even a brave — attempt to put an end to the Catalan crisis, offering a way out of a damaging impasse for Spain. It also testifies to the positive role that amnesties can play in democracies. In our current era, defined by impunity and democratic backsliding, amnesty might appear to be a backward step. But it should always be an option available to political leaders to confront moments of crisis. Nothing comes remotely close in advancing peace and reconciliation.

Political amnesties have a long, noble history dating back at least to the murder of Julius Caesar in 44 B.C., which prompted the philosopher Cicero to ask the Roman Senate to consign the memory of the murder to perpetual oblivion. In more recent times, nations have relied on amnesty to find a way out of political jams and, however imperfectly, to move forward. The 1660 Act of Indemnity and Oblivion accompanied the end of the English Civil War, part of the rebuilding of the English Restoration. In America the Amnesty Act of 1872, which removed most penalties imposed on former Confederates, including the prohibition of the election or reappointment of any person who had engaged in insurrection, rebellion and treason, contributed to Reconstruction.

Amnesty played a leading role in bringing down the curtain on South Africa’s apartheid regime. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which was established in 1995, famously traded truth for justice by granting amnesty from prosecution for those willing to testify fully. For the commission’s chairman, Archbishop Desmond Tutu, amnesty was an essential component of the reconciliation process because of the promise it held for securing the truth and for healing the social divisions created by apartheid. Amnesty, in the form of prisoner releases, was also part of the 1998 Good Friday Agreement, which ended the three decades of violence in Northern Ireland known as “the Troubles.”

Less known is that a sweeping political amnesty began Spain’s transition to a full democracy after four decades of authoritarian rule. The Amnesty Law of 1977 covered all political prisoners, including Catalan and Basque nationalists, as well as the members of the Franco regime. This law is seen as the linchpin of Spanish democratization, and rightly so. Aside from putting a symbolic end to the Spanish Civil War, a bloody conflict that ended in 1939, it enabled most of the political compromises found in the 1978 Constitution — including the incorporation of the Spanish monarchy into a democratic framework, the separation of church and state, and the provision that allowed for the partition of Spanish territory into self-governing regions.

To be sure, there was a big downside to the 1977 amnesty. It helped conceal the so-called Spanish Holocaust, the wave of political reprisals undertaken by Gen. Francisco Franco against the defeated Republicans at the end of the civil war, including thousands of executions and the creation of concentration and labor camps where many prisoners died of neglect and malnutrition. Spain eventually addressed this dark history in 2007 with the Historical Memory Law, which offered reparations to the victims of the civil war and the dictatorship. But amnesty for the old regime was upheld. It was necessary, everyone agreed, for putting the past to rest.

It is disheartening that many who will benefit from the Catalan amnesty law have shown no remorse for their actions. Mr. Puigdemont remains unrepentant and his party, Together for Catalonia, or Junts, has not ruled out holding another illegal referendum. But the most important beneficiaries of the new law are not the radical separatists who violated the Spanish Constitution but rather the vast majority of Catalan and Spanish people who want to put the separatist drama behind them. This amnesty is for them, though they may not see it that way now.

For one thing, the amnesty law is likely to bolster political stability in Catalonia. It undercuts the argument among some separatists that Madrid is incapable of clemency and compromise, robbing them of a rallying cry, and is sure to strengthen the moderate wing of the Catalan separatist movement, which has embraced negotiation as the only viable route to securing independence. As support for Catalan independence declines, the amnesty will also allow Spain to show the world, appalled by the violence that accompanied the referendum, that it is moving on.

Mr. Sánchez’s amnesty deal stands in striking contrast to what his opposition is proposing. The playbook for defeating separatism in Catalonia deployed by the conservative People’s Party and the far-right Vox hinges on prosecuting people for nonviolent offenses, banning separatist parties and rallying the Spanish electorate against Catalonia. It’s hard to see how anything other than rancor and division can come from that approach. Amnesty, with all its messiness, imperfections and compromises, offers a better remedy for democratic coexistence in Spain — and perhaps elsewhere.

Omar G. Encarnación is a professor of politics at Bard College and the author of “Democracy Without Justice in Spain: The Politics of Forgetting,” among other books.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: [email protected].

Follow the New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, X and Threads.