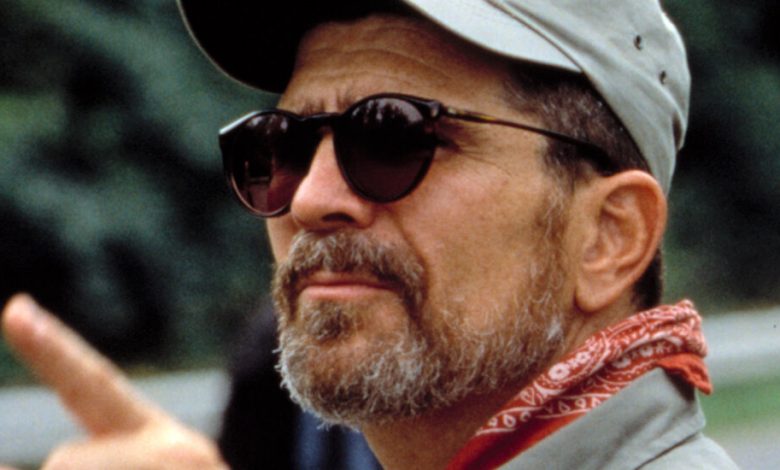

David Mamet, a.k.a. ‘Embittered Dave,’ Would Like a Word

EVERYWHERE AN OINK OINK: An Embittered, Dyspeptic, and Accurate Report of Forty Years in Hollywood, by David Mamet

David Mamet’s best plays have impeccable titles: “American Buffalo,” “Glengarry Glen Ross,” “Speed-the-Plow,” “Oleanna.” So does his best nonfiction book, “Writing in Restaurants.” Now, late in his career, comes a miscellany called “Everywhere an Oink Oink.” Oh, boy. Here we go.

Sometimes you can judge a book by its title. “The more brainless a book’s intended readership, the more rib-nudgingly cute the title has to be,” James Hamilton-Paterson wrote in “Cooking With Fernet Branca,” his terrific comic novel from 2004. Mamet’s new one isn’t brainless. It’s just random, his mind on shuffle. It’s under-argued, rabid in its anti-wokeness and haphazardly written. Mamet’s idea of a transition nowadays is to write, “Anywaythzz (as Daffy said).” Reading this is not unlike sitting next to your Fox News-watching Uncle Alvin at Thanksgiving.

There is a difference, however, between Mamet and the typical post-Trump conservative commentator. (Mamet, who now writes for the National Review, has called himself “a reformed liberal.”) The difference is that Mamet has a hinterland. He’s written important plays and screenplays; he’s got a well-stocked mind; he has a self-deprecating sense of humor. I was willing to put up with his loose elbows, his belching, his dandruff and the way he repeats himself because he’s interesting and funny, at least a portion of the time.

You may not be able to put up with him. If drive-by remarks about “Diversity Capos” and “Covid annoyers,” cracks about liberal policies on immigration and the homeless,and a declaration that we know a movie villain now “by his white skin” will sink this one for you, so be it. Mamet has largely thrown away his career over this stuff, he acknowledges, “sidelined because of my politics (respect for the Constitution, etc.).”

The way to enjoy a meal seated next to someone you mostly disagree with, especially if they’re old (Mamet was born in 1947) and grouchy, is to look for the best in him — to seek common ground. So the rest of this review is going to be a bonsai-size rave, because I have a soft spot for this kind of throwaway, variety-hour book, of which Willie Nelson has also written several.

Mamet, like Nelson, deplores corporate fat cats and their minions, the guys with the roller bags. At least a quarter of Mamet’s book is an attack on film “producers” who do nothing but meddle and stamp their logos, as if they were graffiti artists, on other people’s work. In his book “The Tao of Willie” (2006), Nelson got off a joke about corporate guys that beats the ones here. “What do a record exec and a sperm have in common?” Nelson asked. “They both have a one-in-a-million chance of becoming a human being.”

In “Everywhere an Oink Oink,” which is subtitled “An Embittered, Dyspeptic, and Accurate Report of Forty Years in Hollywood,” Mamet works hard to be epigrammatical. He sometimes succeeds: “Directing a film is like playing chess while wrestling”; “I am willing to think ill of anyone, so I suppose I have an open mind”; “A laugh, like a lascivious glance, cannot be recalled”; “Hollywood is where Nope Springs Eternal”; “If you put cilantro on it, Californians will eat cat [expletive]”; “I’ve always found the Pacific Ocean a bore”; “never trust a Jew in a bow tie.” Chivalrously, he gives several of the best lines to his wife. She refers to money, we are told, as “shoe coupons.” What kind of dog did she want? The kind that “if you walk it, it dies.”

What warmth there is in this book derives from his love for, and encyclopedic knowledge of, old movies, especially noir. He will make you long to watch or rewatch films like Sidney Lumet’s Cold War thriller “Fail Safe” (1964), Jules Dassin’s heist film “Rififi” (1955) and the 1946 version of “Razor’s Edge,” with Tyrone Power and Gene Tierney and Anne Baxter. The last time Mamet cried was during the film “Random Harvest,” with Ronald Colman and Greer Garson. He adds: “Filmed 1942, tears 1970.”

He relates, strange but true, his favorite World War I music hall songs. He quotes Tolstoy’s observation that a marriage is in trouble when the partners begin enunciating very clearly. There are tangents on Dorothy Parker and Preston Sturges and Frances Farmer and Barbara Loden and the poet Donald Hall and Frederick Law Olmsted.

He reminisces about the making of his old movies. His misses directing. He likens it to leading an army into combat. He has directed 10 features, he writes, and written 40 or so scripts, though only half got made. He lists the films he was fired from. He regrets turning down offers to write screenplays for Martin Scorsese and Sergio Leone.

Mamet played four-handed piano with Randy Newman. He flew with Harrison Ford in his plane. Stanley Kubrick was his phone pal. He writes about Debra Winger’s high-stakes blackjack games with Teamsters on a set, and he sends up those same Teamsters by writing that they seem to be limited, while on the job, to three responses: “Whoa, Hey and Alright.” There is a good deal here about his friend, the magician Ricky Jay. Scenes are set, like the time Ridley Scott and Dino De Laurentiis flew in to see him on Martha’s Vineyard to ask him to write the script for “Hannibal.”

Mamet says he was a “straight arrow” on his film sets. That is, he never slept with his female stars. Mike Nichols, he tells us, gave him this advice: It is OK to sleep with your star, but it is not OK to stop sleeping with her.

Mamet doesn’t like it that guys in old movies drink so much milk. He doesn’t like it that judges in movies are always threatening to clear the courtroom but never do. Why do people in movies never re-cork their bottles? It is gratuitous wokery, in his estimation, that “Best Boy” is now “Head Gaffer” on film sets. Clamorous victims, out of his face! He judges men by their handshakes. About this predilection, he writes: “As the Cake, so is the Wedding.”

About his utter lack of Zen, he writes, “Oh, embittered, embittered Dave.” He refers to himself as “the Hermit of Santa Monica, shunning a world that has moved on, and to which his name is as the mention of Herodotus to illiterate youth.” Herodotus knew that aging out of the things you love is awful. The bitterest misery, he wrote, “is to know so much and to have control over nothing.” Herodotus probably hated the new kids in town, too, because they were there to replace him.

EVERYWHERE AN OINK OINK: An Embittered, Dyspeptic, and Accurate Report of Forty Years in Hollywood | By David Mamet | Simon & Schuster | 237 pp. | $27.99